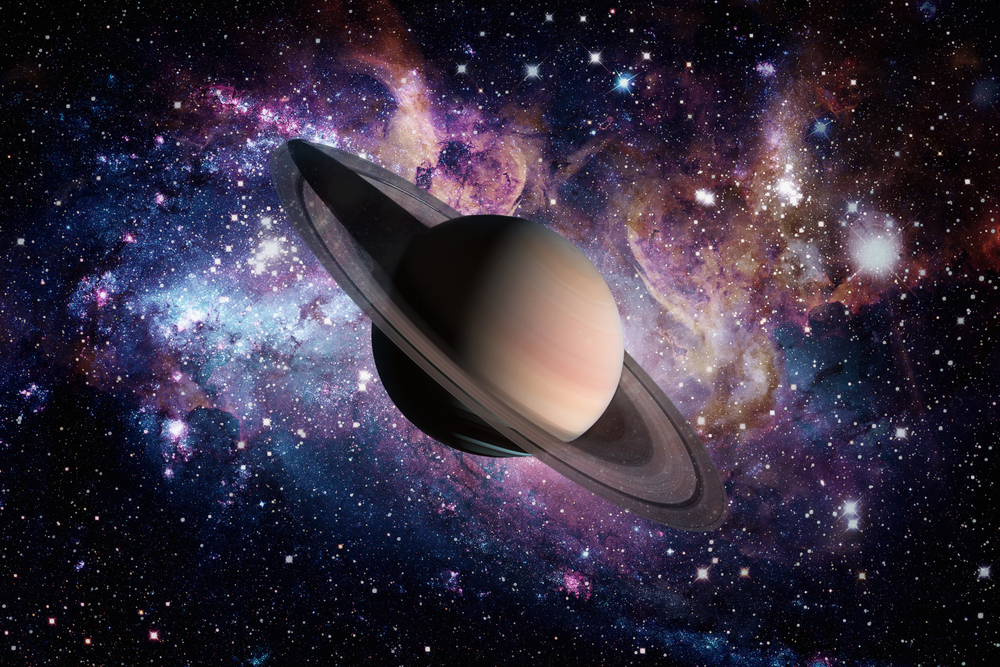

Saturn, the sixth planet from the sun, is the second largest after Jupiter. It can be seen without a telescope and has been known to men for thousands of years. The Romans called it Saturn, after the god of time and the harvest. But it was Galileo Galilei who first saw it through a telescope. But in 1610, his telescope was so primitive that he could not distinguish the glorious rings, only that the planet appeared to have handles on each side. When he looked at the planet a couple of years later, he noted that the ‘shoulders’ had disappeared. They reappeared in 1616, looking like handles on either side of Saturn.

It wasn’t until 1656 that Christiaan Huygens of Denmark came up with the answer. The ‘handles’ were actually huge rings circling the planet at an angle. And when Saturn was in a particular orientation to the earth, the rings were side-on to us and could not be seen. About once every fifteen years, the rings ‘disappear’ to us. While the rings are immense, about 180,000 miles across, the depth of the rings is only about a mile, which is miniscule at that distance. Huygens was also the first man to see that Saturn had a moon, which became known as Titan.

Scientists thought at first that the rings were one solid ring. James Clerk Maxwell pointed out that if the ring were solid, it would break apart due to Saturn’s enormous gravitational pull. He postulated that the rings were made up of billions of small objects in orbit around the planet.

In 1675, the French scientist, Jacques Dominique Cassini noticed thin black lines running around the ring. He had the advantage of new and improved telescopes at the Paris Planetarium. He suggested that Saturn had not one, but seven rings with empty areas in between them, which were the thin black lines.

Slowly, grudgingly, Saturn has given up its secrets to scientists over the centuries. With better telescopes, they began to discover that Saturn had many more moons than just Titan. Cassini found four more major moons: Rhea, Tethys, Iapetus, and Dione.

Centuries passed before much more was discovered about the ringed planet. It was the flyby spacecraft, Pioneer 11 in the 1970s and Voyagers 1 and 2 in the early 1980s that got the first close looks at the planet.

In July of 2004, the Cassini explorer craft arrived on scene and the first real exploration of the system began. Cassini made hundreds of flybys of the moons. It sent a probe named Huygens to the surface of Titan, finding huge oceans of methane and ethane with a surface temperature of -290 degrees F. Chilly!

Enceladus, another of Saturn’s many moons, is thought to have a subterranean ocean, based on multiple flybys by Cassini. And scientists think that there may be life, albeit microscopic life, in that ocean.

Cassini also found a hurricane at Saturn’s North Pole. The hurricane is fifty times bigger than any earthly storm with winds four times as fast. It also doesn’t move. The hurricane just sits at the North Pole and churns.

Cassini went out in a blaze of glory, plunging into the wild gaseous clouds of Saturn in 2017. This ‘Grand Finale’, as it was dubbed, consisted of sending the spacecraft dipping in between the rings before heading into the atmosphere of the planet. The little spacecraft continued to come up with surprises, demonstrating that the ‘ring rain’, a rain of particles down from the rings, was much more complex that the hydrogen and helium they expected. Instead complex molecules, including water ice, nitrogen, methane, and organic appearing breakdown products were found.

Cassini also found twenty more moons in Saturn’s rings, bringing the total to 82, although many are still awaiting verification of moon status. Saturn now surpasses Jupiter for the most moons in the solar system.

The next big Saturn mission is Dragonfly, which is scheduled for takeoff in 2026 for the purpose of exploring Titan. Dragonfly will arrive at Titan in 2034.